Archaeology and African American Cultural Heritage

In honor of Juneteenth, we discuss ongoing work representing underrepresented communities uncovered by archaeology. We highlight investigations at Mulberry Row in Virginia, and we discuss the work of Angela Jaillet-Wentling in Mercer County, PA at the Pandenarium site, just north of Pittsburgh.

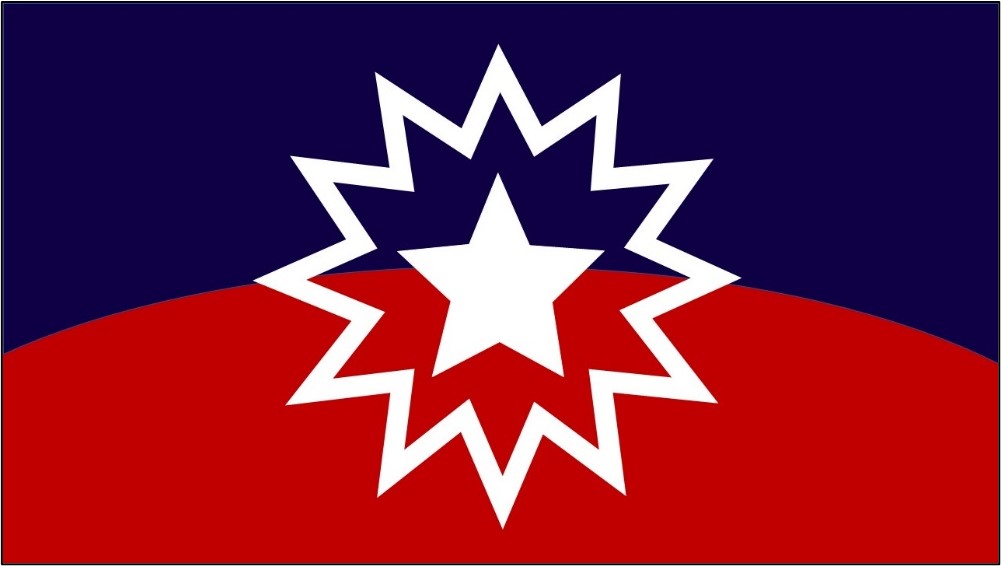

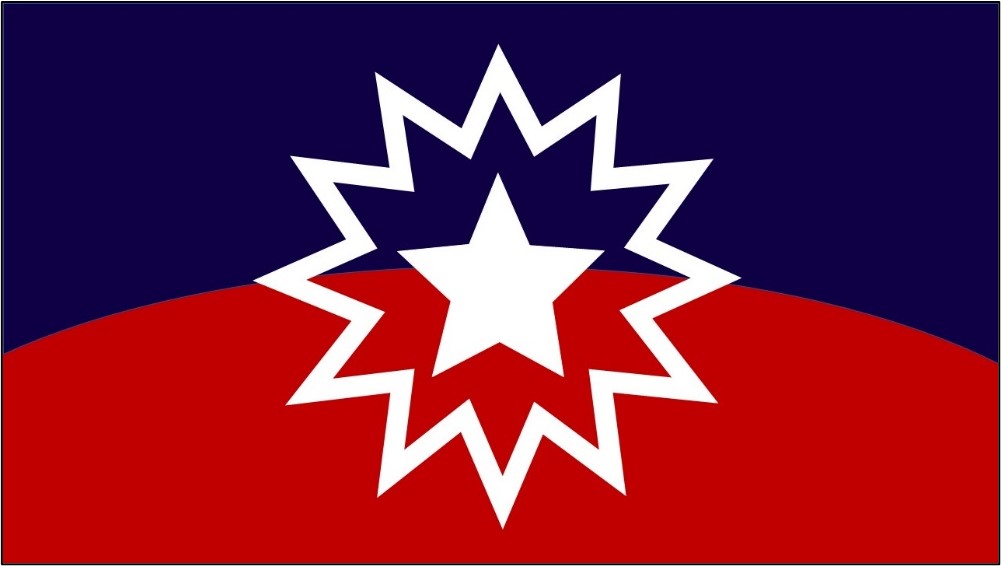

Juneteenth, our nation’s newest federal holiday, celebrates and honors the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Roughly two years after the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln, Juneteenth celebrations began when news of emancipation reached Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865.

Can you imagine how that moment was? How do you think you would have reacted? Would you believe the news that you were suddenly free? Would you trust the messenger or think there was something nefarious afoot? Would you have been anxious about the future for yourself and your family? Can you imagine the joy and celebration? These questions are the kinds of questions that cross my mind when I get deeply involved in creating a research plan to evaluate archaeological sites. I think about the moments lost in the past. I wonder what answers we can find when we look at things a little differently and dig a little deeper.

Archaeologists in the United States have studied African American archaeology and African Diaspora since the latter half of the twentieth century. They investigate historic landscapes, sites, features, and artifacts representing African American cultural heritage dating from the colonial era through the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Archaeology gives us a unique way to explore the parts of our past that are by-in-large absent from historical documents…with the goal of finding a truer account of American history.

In celebration of Juneteenth, I will discuss cultural resources work from Mulberry Row at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Albemarle County, Virginia, and the Pandenarium archaeological site here in western Pennsylvania, as well as the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act (AABGPA).

Archaeological work at both sites has expanded our understanding of the struggles and triumphs in the daily lives of the folks that lived and worked at these sites. Archaeology at each site has included more than down-in-the-dirt excavation. Investigators have worked to build new collaborative networks of community members, professionals in the arts and sciences, and involved descendants of the people who lived at the sites. They have engaged the public about the interpretation of the sites. They have also used modern tools, and technology (e.g., ground penetrating radar [GPR], light detection and ranging [LiDAR]) in their studies and have found meaningful ways to engage the public.

Mulberry Row

At one time, Mulberry Row was home to enslaved people and free black and white workers for more than 50 years (c. 1770-1826). It was the center of activity at Jefferson’s Monticello and essentially the place that grew Jefferson’s economic industries and wealth (Montichello.org 2022).

Archaeological excavations at Mulberry Row identified architectural remains (i.e., subfloor pits and post holes) and artifacts (i.e., bottles, broken dishes, personal items) that were associated with the location of the small homes where enslaved men, women, and children lived. From the results of these excavations, historic preservationists at Monticello were able to construct a cabin like the home of Priscilla and John Hemings on Mulberry Row. The Hemings spent nearly 19 years apart from being traded between different family members and work sites but found ways to remain connected in their relationship and love (see the link to Hemings Cabin video below [Montichello.org 2022]).

I cannot discuss Mulberry Row without mentioning one of my favorite historic women, the clever and altruistic Sally Hemings, who, at age 16, negotiated for the freedom of her future unborn children. Sally was born into slavery and was property inherited by Thomas Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles (Sally was also Martha’s younger half-sister). Sally Hemings is famously known as Jefferson’s concubine, but she was so much more than Jefferson’s paramour. As a young teenager, Sally lived in Paris with Jefferson and other members of his family for nearly three years. Under France’s laws, Sally was a free person. Yet, Jefferson desired her and implored her to return to Virginia. Sally negotiated for her privileges and the freedom of her children. After returning to Mulberry Row, Sally gave birth to her and Jefferson’s first child, who did not live. Sally and Jefferson had four more children who were born enslaved and later freed. Excavations at Mulberry Row recovered a French apothecary jar near one of the quarters that may have been where Sally lived (see the link to the Sally Hemings virtual exhibit below [Monticello.org 2022]).

Pandenarium

My friend and colleague, Angela Jaillet-Wentling, conducted archaeological research at Pandenarium in Mercer County, Pennsylvania (Photograph 2). In her 2021 must-read article Piecing Together Pandenarium: Archaeology at the Site of a Free Black Community in Western Pennsylvania, Jaillet-Wentling describes the history and archaeology of Pandenarium.

The Pandenarium site represents an antebellum community settled in 1854 by free African American men, women, and children who traveled from a plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia (not far from Monticello). Abolitionists in Mercer County built houses and planted orchards for their new neighbors, essentially following the layout of a northern village community. When the newly freed families arrived, they modified their landscape, changing their space to create their homes (Jaillet-Wentling 2021).

Jaillet-Wentling used GPR, LiDAR, shovel test pit (STP), and test unit excavation to analyze the site. She compared the site layout of Pandenarium to two communities in Mercer County, Hadly and Mercer, and to two plantation settings in Virginia, Belmont, and Monticello. The African American residents chose to organize their community in a way that represented inclusion with their white neighbors. The community layout showed similarities to Hadley and Mulberry Row. Jaillet-Wentling identified the locations of several residences representing three generations of the John and Rosie Allen Family (Jaillet-Wentling 2021).

Jaillet-Wentling worked with a collaborative network of historians, authors, archaeologists, faculty, and students at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP). Through collaboration, descendants of the original Pandenarium community visited the site. They are now involved in its future. In 2020, a historical marker was installed near the site in Mercer County, briefly telling the story of Pandenarium (Jaillet-Wentling 2021).

African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act (AABGPA)

The effort to have Juneteenth recognized as a federal holiday has been decades in the making. Other national efforts like the AABGPA create a system of action to honor African American cultural heritage. The AABGPA was introduced to Congress on February 2, 2022. The bill is currently making its rounds through subcommittees and waiting patiently to be signed into law (Congress.gov 2022). If passed, the AABGPA will create the United States African American Burial Grounds Preservation Program within the National Park Service (NPS). The program will likely provide funds to governments (i.e., federal, state, local, tribal), historic preservation groups, and other public and private organizations to identify, preserve, restore, interpret, research and document historic African American burial grounds. This newly proposed legislation garnished interest and support from many people of different backgrounds (e.g., archaeologists, historians, genealogists, all kinds of folks). We are waiting excitedly for the bill to be passed into law.

An Inclusive Story

At the end of the day, archaeologists are essentially storytellers. African Americans’ rich and complex history is an essential part of our nation’s shared story. Now more than ever is the time to seek stories of underrepresented people and communities and do the work to make our shared heritage inclusive, better understood, and more accessible.

I am grateful Juneteenth is a federally recognized holiday. Celebrating Juneteenth is a way to communicate our sense of the past to the future. Juneteenth gives us a moment to reflect and appreciate how much we have to cherish.

I am also proud to mention that Big Pine Consultants recognized and celebrated the Juneteenth holiday before the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act was signed into law. So, I will be off enjoying the holiday on Monday.

Worthwhile links to click:

Watch this video about the Hemings Cabin at Mulberry Row

Learn about the life of Sally Hemings

Read Angela Jaillet-Wentling’s article: Piecing Together Pandenarium

Pandenarium: Unearthing Black Settlers’ Stories – IUP News

Slavery | Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

African American Burial Ground Preservation Act.

Citations:

Congress.gov.

2022 “H.R.6805 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): African-American Burial Grounds Preservation Act.” February 2, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6805. Accessed June 13, 2022.

Jaillet-Wentling, Angela

2021 ‘Piecing Together Pandenarium: Archaeology at the Site of a Free Black Community in Western Pennsylvania’s, in Pennsylvania Heritage, Spring 2011. https://paheritage.wpengine.com/article/piecing-together-pandenarium-archaeology-at-the-site-of-a-free-black-community-in-western-pennsylvania Accessed June 10, 2022.

Kaur, Harmeet

2022 “The Juneteenth flag is full of symbols. Here is what they mean.” https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/17/us/juneteenth-flag-meaning-explainer-cec/index.html. Accessed June 17, 2022.